This is a segment from The Breakdown newsletter. To read more editions, subscribe.

“We are not measuring the world, we are creating it.”

— Niels Bohr

Two of history’s greatest minds — Albert Einstein and Niels Bohr — disagreed on the fundamental nature of reality.

Is the world around us, as Bohr argued, created only when we observe it?

Or does reality exist independently of our gaze, as Einstein believed?

The two greats debated it throughout the 1920s and ‘30s, and their disagreement has remained central to quantum mechanics ever since — forcing physicists to grapple with what their mathematical equations tell us about the nature of reality.

Until this week, when the debate was settled in favor of Bohr.

By bouncing a single photon off just two atoms, scientists at MIT showed that the behavior of the photon (wave or particle) remained unsettled until they had measured it.

This confirmed Bohr’s belief that observation is not simply a passive act of seeing what already exists, but an active process of creating the very thing being observed.

In other words: Observation changes the system being observed.

This is how markets work, too.

“Financial markets constantly anticipate events, both positive and negative,” George Soros wrote, “which fail to materialize exactly because they have been anticipated.”

For example: The US labor market is weakening, but because the Bureau of Labor Statistics observes it for us every month, markets have reacted in a way that will change the labor market.

After the BLS report this morning, 10-year Treasury yields fell 20 basis points, and Polymarket odds of a Fed rate cut jumped 15 percentage points.

Moves like these can change things: The more that markets anticipate a recession, the less likely a recession becomes.

It works in the other direction, too.

At one point this week, each of the four AI hyperscalers — Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta — were valued at over $2 trillion.

In total, the stock market is assigning $10 trillion of market capitalization to those four, based on the observation that they’re likely to be among the primary beneficiaries of next-generation AI.

If so, the act of observing the trend in AI will have played a large part in making AI happen.

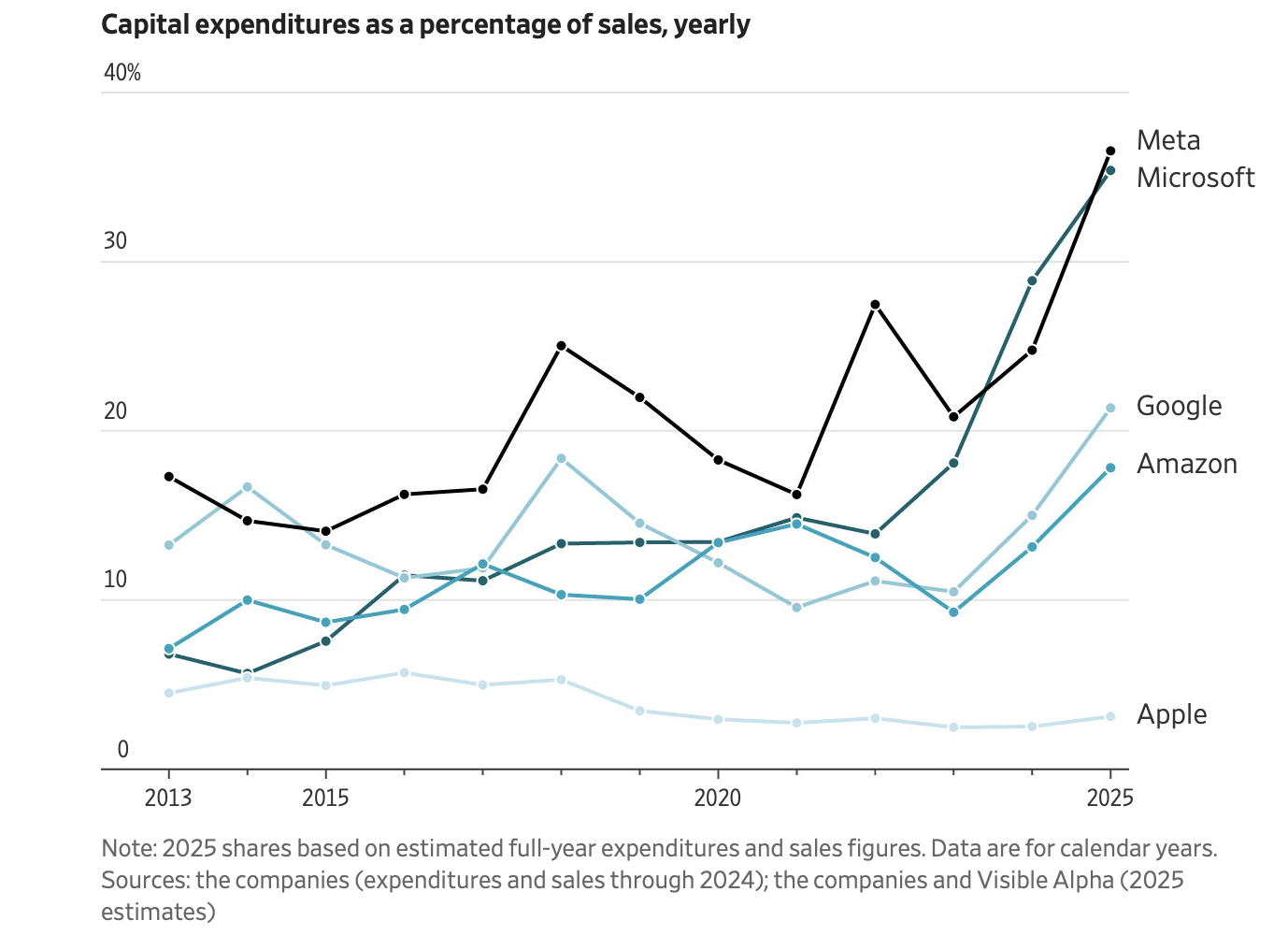

Morgan Stanley estimates the four hyperscalers will invest $2.9 trillion in AI capex between 2025 and 2028, but that they’ll be $1.5 trillion short of cash needed to fund it.

Only the massive valuations markets have granted them will make up the difference.

In that sense, what AI becomes will depend, at least in part, on the market’s observations and predictions about it.

Sam Altman, for example, predicted this week that we’re on a path to “superintelligence” — self-improving AIs that exceed humans in every domain.

“It’ll give people incredible superpowers that were sort of science fiction only a couple of years ago,” he optimistically predicts.

It may already be happening: “Over the last few months, we’ve begun to see glimpses of our AI systems improving themselves,” Mark Zuckerberg said on Wednesday, adding that “superintelligence is now in sight.”

The pace of this self-improvement may be about to accelerate.

Also this week, a team of researchers released an open-source model that “enables AI to conduct its own architectural innovation.”

Experts say this will transform AI research “from a human-limited to a computation-scalable process.”

In other words, AIs will now be bounded only by the amount of computing capacity that humans choose to give them — and the stock market, having observed the trend, is choosing to give them trillions.

Not even Niels Bohr could tell us what the consequences of that observation will be.

Let’s observe some charts and see what else happens.

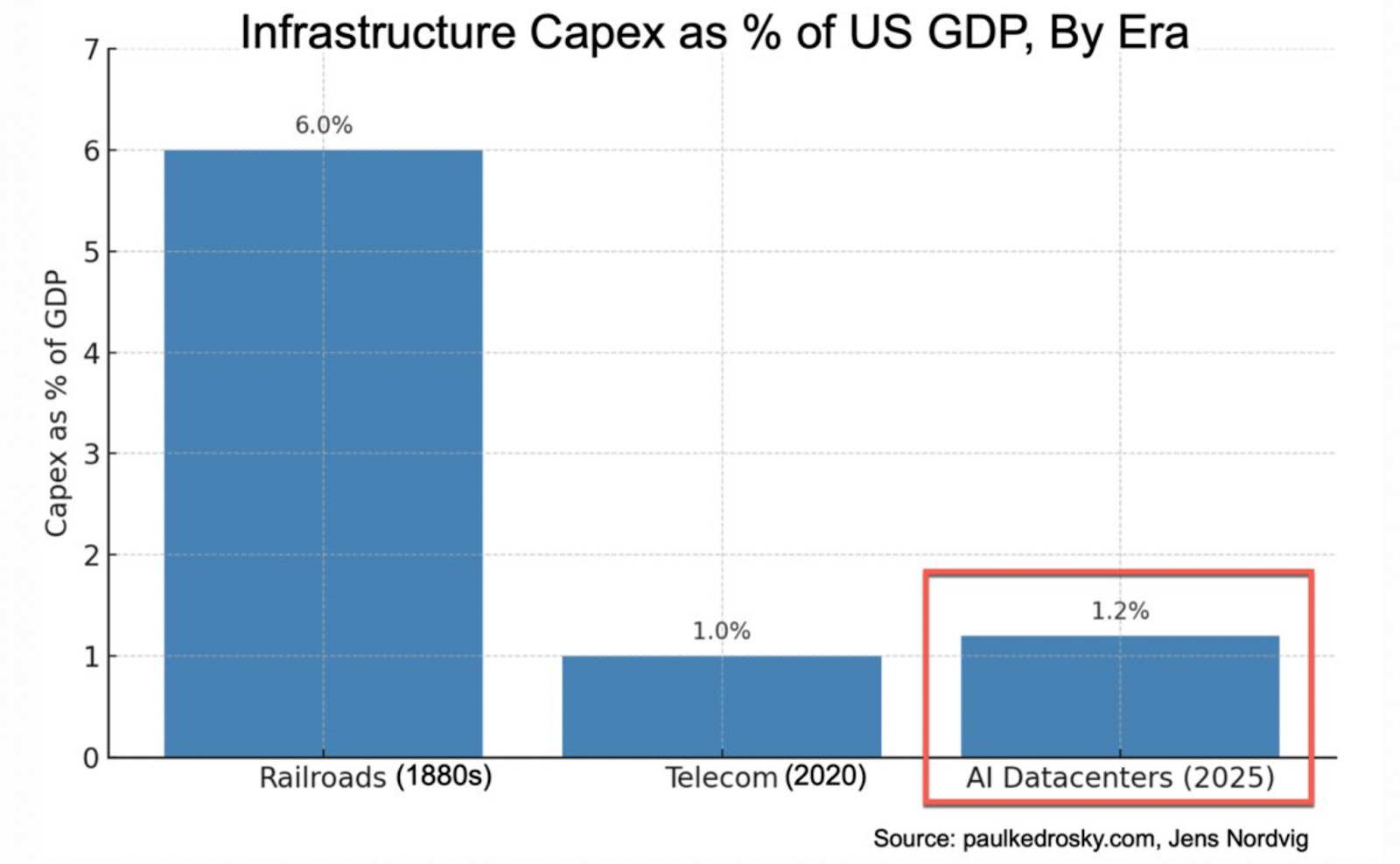

The AI capex boom:

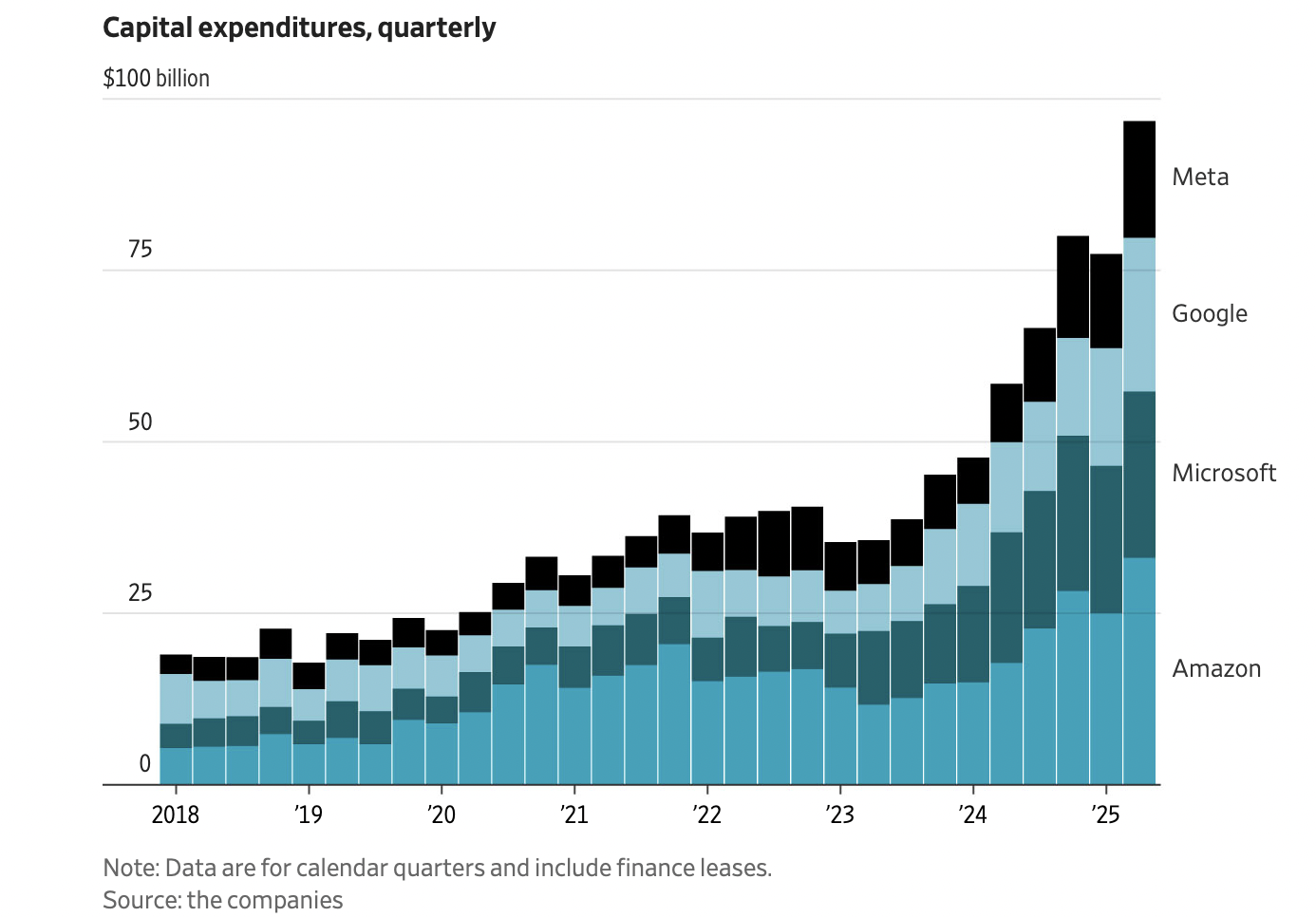

The Wall Street Journal documents the surge in capex among the four hyperscalers, which are on pace to collectively spend $400 billion this year alone.

Going all in:

The hyperscalers are both making more money and spending more of it on capex.

This morning’s unemployment data:

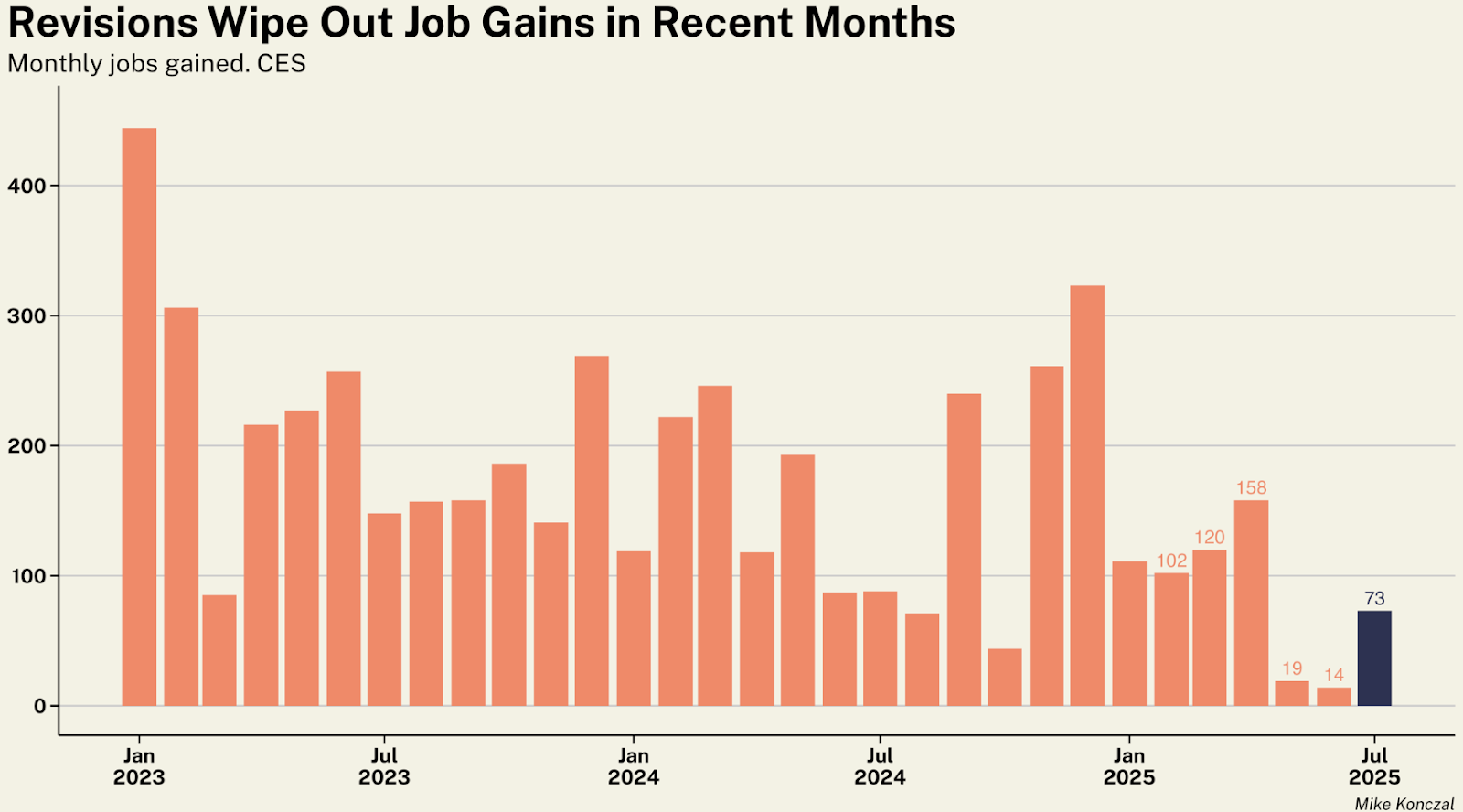

The US economy is estimated to have added only 73,000 jobs in July. But the shocker in this morning’s report was the 253,000 downward revision to the prior two months, taking the three-month average down to just 35,000. An economy that seemed surprisingly resilient suddenly looks unsurprisingly fragile.

Contrary to popular belief…

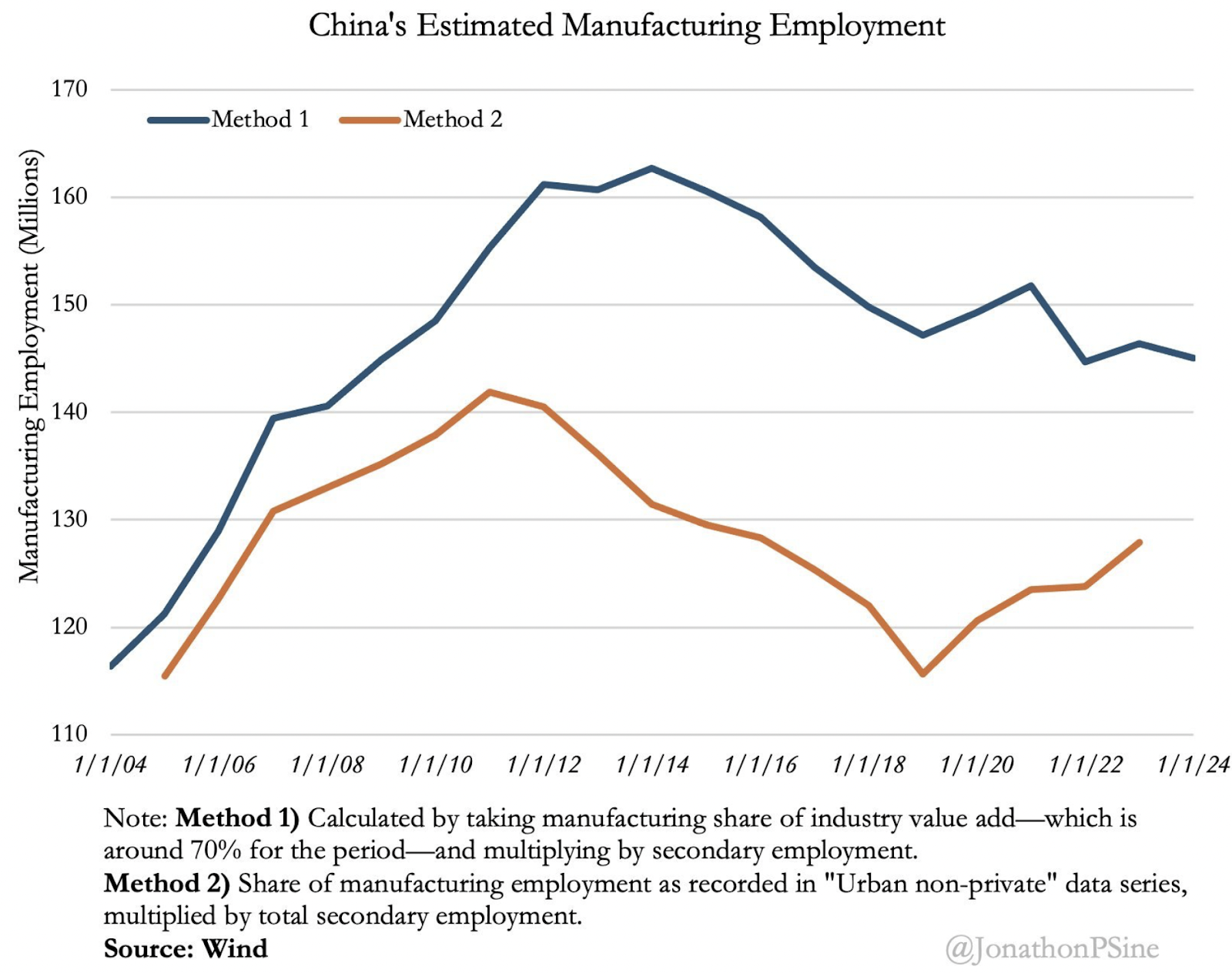

…the jobs do not seem to be going to China. Data from Jonathon Sine shows that “China shed the equivalent of the entire US manufacturing sector (~15 million jobs) over the last 15 years.”

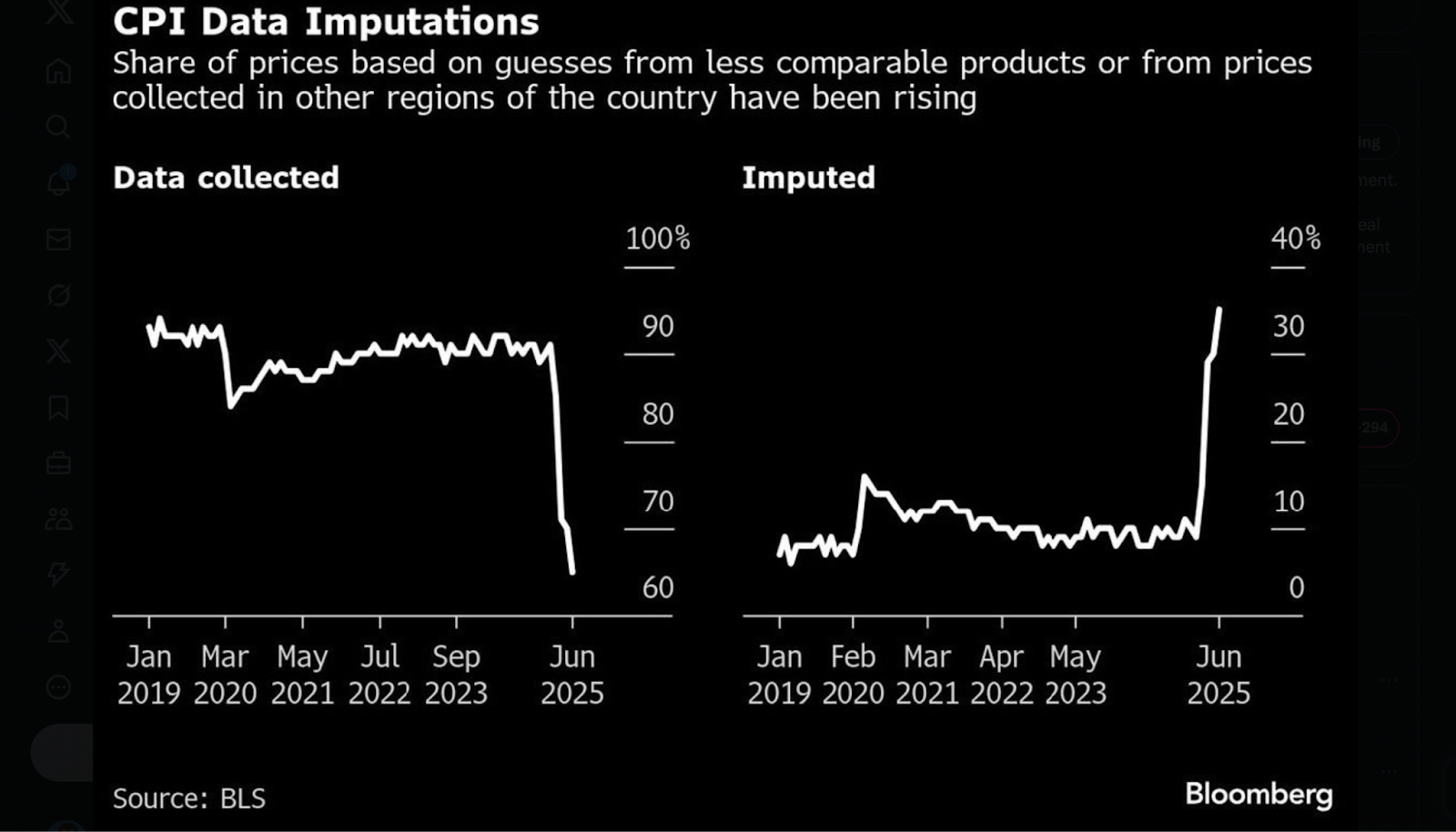

Inflation estimates are more of a guesstimate now:

Thanks to funding cuts, the Bureau of Labor Statistics is collecting less inflation data, which means that a bigger portion of CPI is “imputed” (aka, guessed) based on the data it did manage to collect.

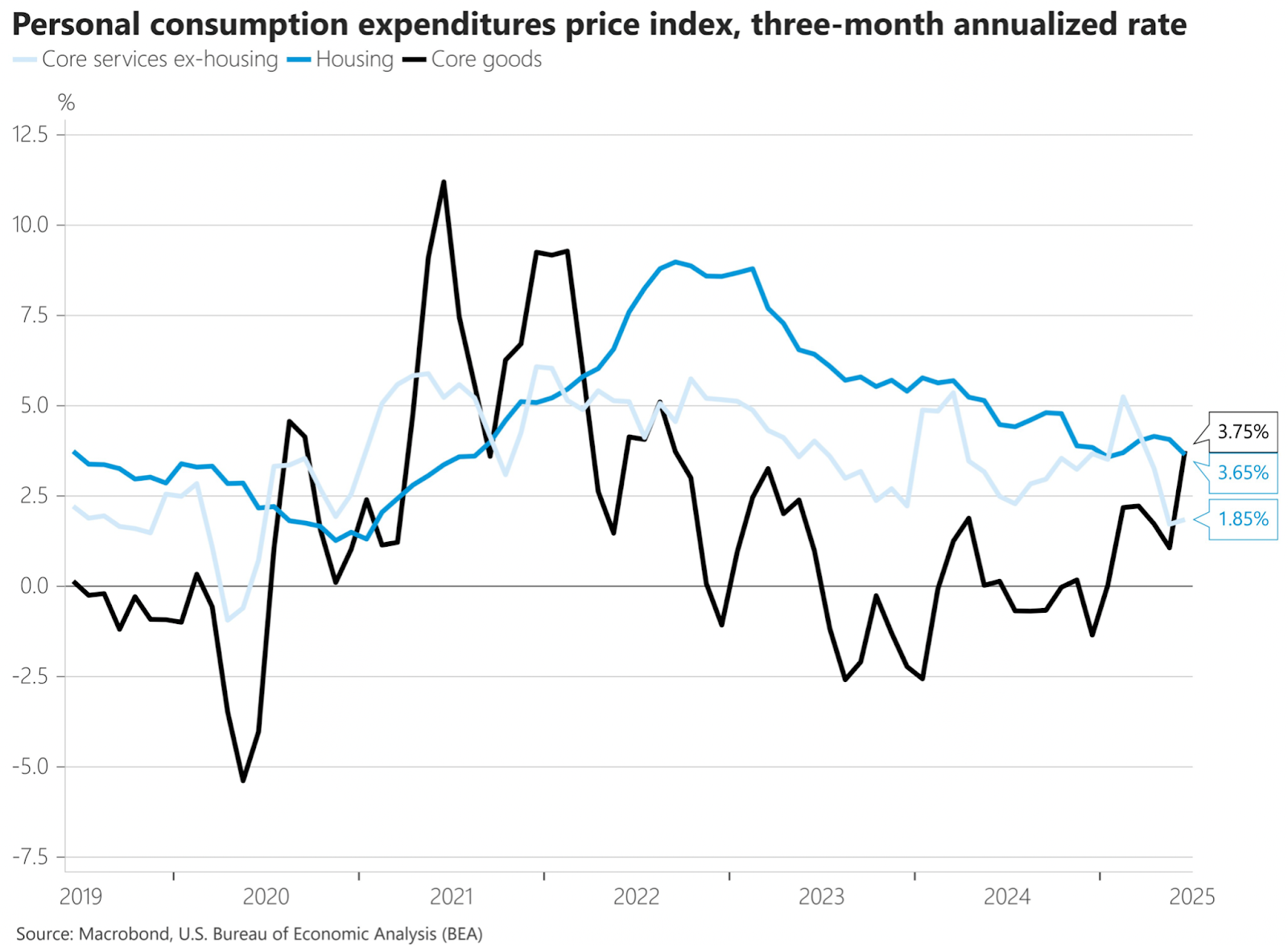

Not out of the inflation woods yet:

The two dissenting FOMC voters will feel vindicated by this morning’s weak jobs report. And the president will be even more irate than he was yesterday. But it might still be hard for Powell and the rest of the FOMC to agree on cuts when the price of core goods are rising at a 3.75% pace.

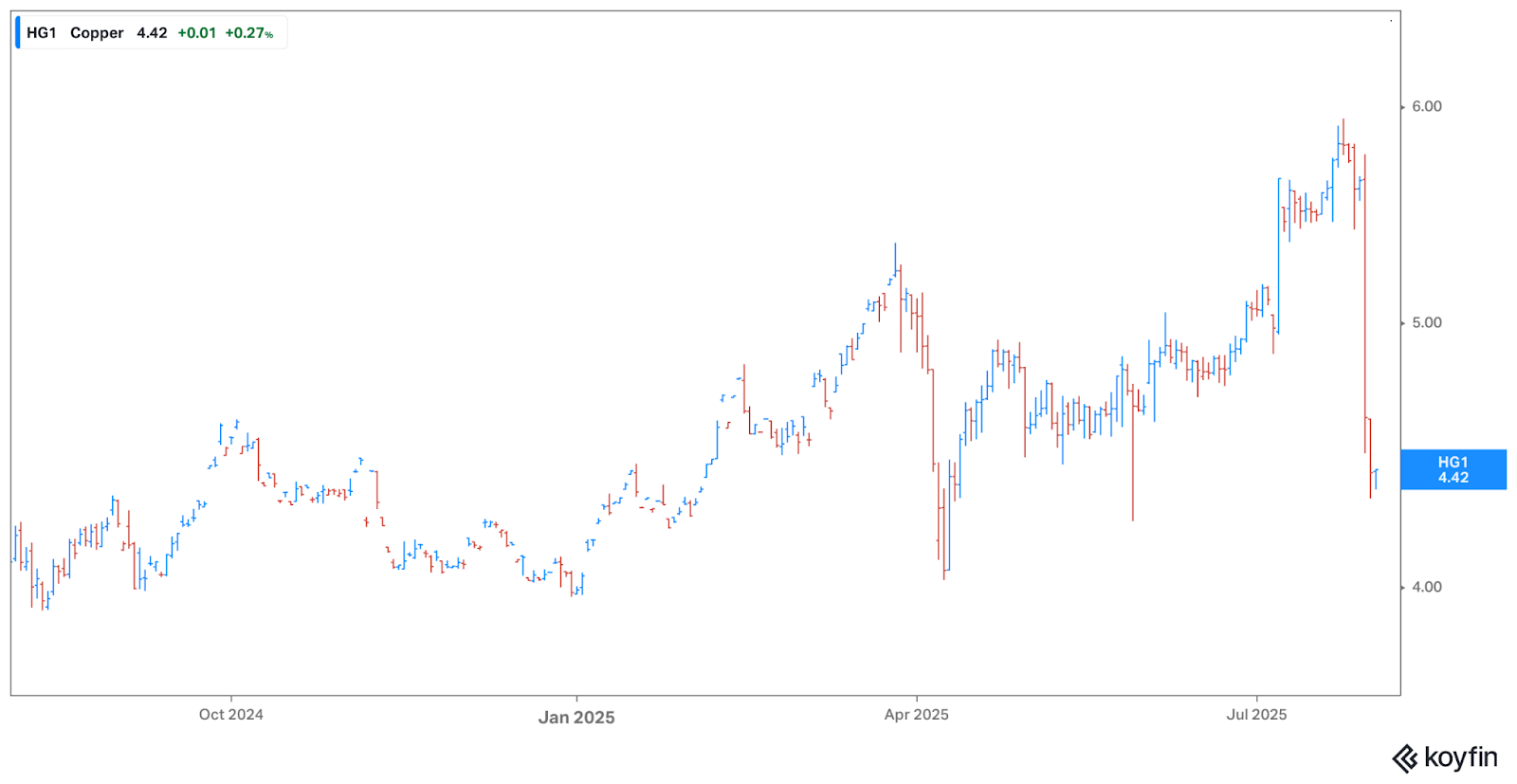

The price of copper is down, at least:

Copper futures fell 20% after it was announced that President Trump’s latest round of tariffs would exclude metals. That kind of whiplash policymaking is good for volatility traders and bad for anyone trying to run a business that requires copper.

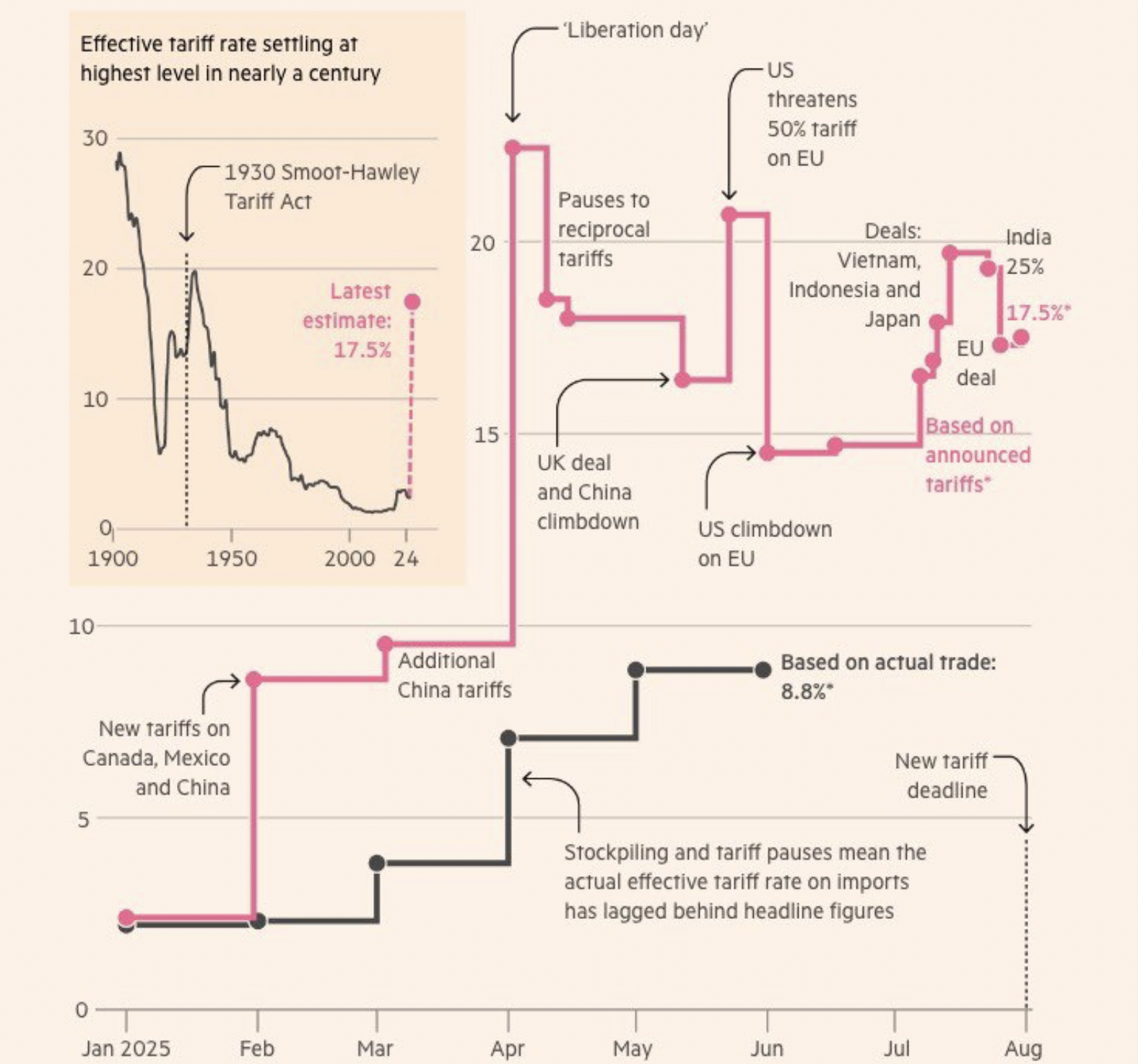

Tariff update:

The pink line is the overall level of tariffs, according to what’s been announced. The black line is what importers have actually paid. The 10 percentage point difference between the two suggests that most of the impact on the economy is still to come.

Railroads next?

blockworks.co

blockworks.co